Nearly there with the door. Coat of primer yesterday, then will move on with glazing. fitting locks, etc. Looking good I think. I need to decide on a topcoat colour. Black would be easiest choice and may well win out, as time is pressing on.

Nearly there with the door. Coat of primer yesterday, then will move on with glazing. fitting locks, etc. Looking good I think. I need to decide on a topcoat colour. Black would be easiest choice and may well win out, as time is pressing on.

I have no idea whether I’m doing this correctly, but it all seems to be going ok. By all means send me tips on how to do this better, or ‘right’. I value the opinions of full-time joiners who do this for a living, especially traditional hand tools workers.

Right, I had a bit of time between the plasterers, electricians and plumbers in the house, so onwards with renovating this old door.

I’m still crazy busy on a house renovation, but one of the projects I’m shuttling back and forth on is sorting out a new front door. The property is a mid-terrace Victorian two-bed, built in 1880. I found a decent door in a reclamation yard locally, for a very reasonable £80.

The current hallway in the house suffers a little from being too dark, primarily because the existing front door has only one tiny fanlight with glass panels.

This new four-panel door will be converted so that the top two panels will hold glass (and a lot more light) into the hall.

I will be fitting frosted safety glass for security reasons and for privacy, and will post more detail about mouldings and fitting as I get round to it.

The glazing bar dowel joint quickly became superseded by the mitred joint. However, the joint itself (and the use of a sash dowelling box to make it) is of some interest to me. It’s actually very simple, as Richard Arnold showed me.

For some time now, I been drawn to the idea of making traditional box sash windows using mainly hand tools. By ‘traditional’, I mean sticking the mouldings of the glazing bars with sash planes, rebating the stiles and meeting rails and chopping out all the mortise and tenons by hand.

One thing that has always confused me. Even though I have now found some excellent sash planes, I still wondered how craftsmen used to mitre the cross joints so accurately.

During bits of research on the internet, I’ve come across some excellent resources, such as this pdf from Tim Nott.

However, some tools that kept cropping up in 18thc-19thc information, was the use of sash templates, or ‘templets’. I sent a query to Brian Read at the excellent Tools and Trades History Society, asking of he knew of anyone who could show me how to use these and perhaps I could photograph a slideshow. (This enquiry applies to anyone else who also happens to read this post. I live in London and would still very much like to watch a joiner who can show me these in use.)

Brian was very helpful and forwarded my request to Jane Rees, who many readers will be familiar with, from her and her late husband’s excellent books about vintage tools.

Jane came back with some great info. To start with, if you were making sash using a template, you would have been expected to have a matching plane, to make a perfect profile to drop into the template. This I didn’t know.

Jane supplied me with some of her pictures showing a matched plane with template, some templates of different styles on their own and also a superb pdf of an article Jane wrote for the Construction History Society (which was later reprinted by the Early American Industries Association). You can download a pdf of the article here (3.22mb).

Once you have a profile that has been cut to for the inside of your template, you can work on mitring, or coping the end of it. Mick Dowling of the HTPAA shed some light on this for me:

The components of a sash are the top and bottom rails, the left and right stiles, and the glazing bars.

If you look at a sash from within the building the intersections of the

moulded part of these components (the fancy shaped bit, lambs tongue for example) appear to be mitred, but are in fact coped. Similar to the way the intersection of skirting boards (the board in a room at the base of wall) in an internal corner looks to be mitred, but is one piece of timber cut to fit (coped) over the adjacent piece.

Coping is particularly the case where glazing bars meet the stiles or rails.

I’ve worked on windows as old as the 1860s and have seen stile/rail

intersections that are simply mitred.

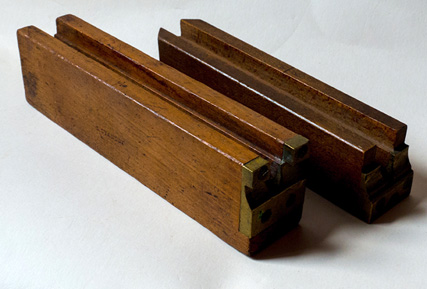

Scribing templates are either double sided to fit over the glazing bar, or

single sided for use on the stiles or rails.

With either of those types there are 2 variations. The ones with brass tips

are square on the end and are used with a coping chisel, and the type that is cut on a 45 is used for marking with a pencil or scribe and cutting out the waste with a coping saw.

Sometimes the single sided ones are screwed together to make a template that fits over the glazing bar. Might have been made that way.

If you’re slightly confused about glazing bars and which way round they face, take a look at an excellent write-up on Zach Dillinger’s blog. He shows you how a sash fillister is used when working on the outer rebates where the glazing would sit. A great page which will explain things much easier than I could do!

(Added 05/10/2014)

David Nelson, a reader of the blog from the US, has kindly sent me a digital copy of his excellent guide ‘English Sash Planes’ and kindly allowed me to add a link to the blog for people to download it. Well worth a read.

You can download a pdf of the article here (11.37mb).